by Charles H. Christiansen, EdD

This month on March 17 we mark the 100th anniversary of the founding of occupational therapy and the inception of the American Occupational Therapy Association. From its roots in mental health to its current broad scope of practice serving a wide spectrum of children and adults who need support for independent living, the field of occupational therapy has become a respected global profession. To help us in recognizing this event, Chuck Christiansen, our resident expert-in-the-field for the NAB offers a brief discussion of this important anniversary and lends some historical context to the celebration

Throughout history, chance alignments of people, events and ideas have led to important social changes. In 1917, an eccentric architect intent on recovering from a disabling illness, and the most devastating war in history coincided to lead to the development of a new profession.

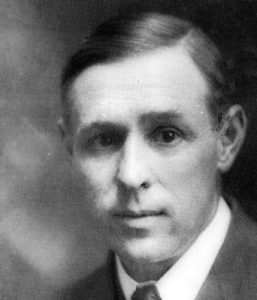

The story begins with George Edward Barton. Born into a privileged family near Boston in 1871, Barton studied architecture and traveled widely. As a man with creative leanings, he developed a key interest in the arts and crafts movement, which advocated a return to hand craftsmanship as a reaction to the depersonalizing consequences of industrialization and urbanization then occurring in the United States.

George Edward Barton

The United States at the Dawn of the 20th Century

This was an era of great corporate wealth generated by a rapidly growing nation. The United States at the dawn of the 20th Century was a country focused on Steel, mining, railroads, timber, manufacturing of all kinds and vast stretches of unsettled land that would lead to great technological and population changes, as well as a sense of national optimism. Even with this great advancement, social problems still emerged as language and cultural differences clashed, and living and working conditions of workers were often harsh and health threatening. The stress of change and working conditions led to widespread stress-related illnesses, which were poorly understood at the time, and a person’s perceived worth was often defined by their ability to work. Large asylums were built to house more severely affected people who had acquired ”psychosomatic illnesses,” what we know as different types of disabilities and chronic conditions, or were unable to cope with the living challenges they faced

This was also a time where Medicine was undergoing great change. At this time, the standards that we often associate with good medicine had not yet been implemented, and the scientific method – a mainstay of the modern medical professional— was not common. The Flexner report, commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation in 1910 to study medical education and address public concerns regarding quackery and inconsistent quality of care, led directly to the development of scientific medicine. There was an urgent need to have a medical system capable of effectively responding to epidemics of flu, tuberculosis and the growing incidence of mental illness. Yet, before reforms took hold, popular “cures” remained as options for care. These included the “fresh air and exercise cure”, the “rest cure”, the “water cure” and the “work cure”, among others.

Consolation House and the Multiple “Cures”

In 1901, George Barton contracted tuberculosis. On the advice of his physician he moved to Denver for the “fresh air cure” where he would benefit from the healing effects of mountain air and exercise. During his time in Colorado, Barton recovered and resumed his architectural practice, soon undertaking a key project in Colorado Springs that involved the design of a private “home” to employ poor children and older adults who were unable to earn a living. This project, which included spaces for gardening, manual labor and craftwork, enabled George Barton to apply his personal interest in the benefits of productive work and hand-crafted labor.

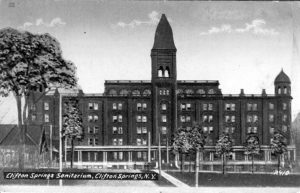

In 1912, while on a survey assignment, Barton suffered severe frostbite that required amputation of two toes. During his recovery, Barton experienced hysterical paralysis, and on the advice of his physician travelled to a sanitarium in Clifton Springs, New York. Many such sanitaria existed, often in the vicinity of natural springs, which were seen to be therapeutic as part of a treatment known as the “water cure.”

Clifton Springs Sanitarium in 1900

In Clifton Springs, Barton became disillusioned about the inability of physicians to help him regain his function. In desperation, he turned to Emmanualism, a healing approach established by Dr. Elwood Worcester of the Emmanuel Church in Boston. The Emmanuel Movement was a philosophy of healing that encouraged the use of body, mind and soul in the recuperative process. A key part of the approach emphasized the importance of purposeful work, and Barton was so encouraged with the potential for this approach that he decided to aid his own recovery by establishing a recuperative center for others. He remodeled his property to include characteristics of the home he had designed in Colorado Springs, and called his new recuperative facility “Consolation House.”

Some of the ideas of adopted by the Emmanuel Movement had earlier been used in mental health care, based on the growing recognition that productive activities were a key component of healthy daily routines. A number of individuals, including physicians and nurses, had advocated, used and written about their belief in using productive activities to aid the recovery process. This use of productive activity was sometimes called “the work cure.”

Emmanualism differed from other work-based approaches because it was tied to religious and spiritual practices. This religious connection and the evangelistic zeal of its proponents gave Emmanualism a reputation as a cult movement. Barton wanted to reform hospitals so that they restored health and returned people to productive living, so he moved away from Emmanualism to types of work-related approaches that were accepted in hospitals and mainstream medicine.

The Gathering

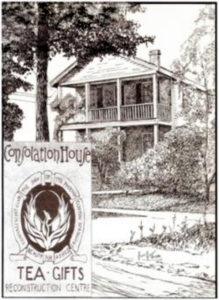

Consolation House sketch with sign

Barton opened Consolation House in 1914, and began receiving referrals of patients from physicians, working with them in his garden and workshop. Barton’s key interest in the therapeutic use of occupations led him to become familiar with the writings of Dr Herbert Hall, Nurse Susan Tracy and Dr. William Rush Dunton, Jr. among others. Barton began corresponding with these experts.

The correspondence between Barton, Dunton, and other key figures working with therapeutic occupations continued, and in 1916, Barton decided to organize a meeting for these advocates of “the work cure”, which he now referred to as “occupation therapy”. The plan was to host these invited experts at Consolation House, and his intention was to create a society to promote “occupation therapy.”

In mid-March, 2017, Barton’s guests arrived to begin the task of organizing a society. Though they had been helpful to Barton, missing from the group were key figures Herbert James Hall, MD; and Susan Tracy. Barton seemed wary of including physicians in the new society, perhaps because he feared that the science-focused, elitist changes that were then happening in organized medicine would create distractions from his objective.

The fledgling National Society for the Promotion of Occupation Therapy was established on March 17, 2017, but, as is so often is the case, this beginning evolved in a quite different manner than he might have predicted.

Founders of the National Society for the Promotion of Occupation Therapy

A Great War was Raging

At the time George Barton gathered his group of occupation experts in Clifton Springs, World War I had already been underway in Europe since 1914. The U.S. had remained officially neutral, but ultimately the German sinking of the British liner Lusitania, (and the loss of 128 American passengers), led to a declaration of war against Germany on April 6, 1917. In American history, there has always been a link between disability and wartime conflict and Occupational Therapy would find much of its purpose during the days of the Great War.

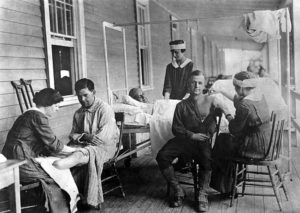

Over the next year, the United States mobilized for war, paying particular attention to planning services for wounded and disabled soldiers who would return from the front lines. During this period, the government agreed to train and hire reconstruction aides to assist with care on the front lines and rehabilitation efforts at home.

Reconstruction aides, which included occupational therapists, were focused on efforts to address the movement or the productive use of wounded limbs. Many were trained and hired to staff a system of rehabilitation facilities in the United States, as well as to support soldiers with less severe injuries behind the front lines. The emphasis on either physical or emotional “reconstruction” ultimately led to the formation of two distinct professions, physical therapy and occupational therapy.

Reconstruction aides- at front and home)

Because of its holistic focus and longer history, occupational therapy was the first of these two aspiring professions to formally organize and ally itself successfully with medicine. Physical therapy soon followed.

Barton’s Departure and 100 years of Progress

As the organizer behind the formal creation of occupational therapy, Barton was elected as its first organizational president. Yet, for unknown reasons, he resigned within a year and decided to focus on his own pursuits. The war and its aftermath created sufficient opportunities to illustrate the therapeutic value of productive activity and rehabilitation programs and the fledgling profession grew.

Key individuals who had gathered at Consolation House forged a closer alliance and nurtured the new organization and profession for more than a decade afterward.

Over time, additional wars, legislation, educational standards and an evolving health care system led to better recognition and more emphasis on a scientific-based practice. Today, many new occupational therapists enter practice with a clinical doctorate, and the field has worked for over a decade on its Centennial Vision project, making significant progress toward its goals to become better recognized, globally connected, more diverse, and characterized by practice that is science-based and evidence driven.

Its leaders are proud that the field now has 150,000 practitioners in the United States, over 250 educational programs, and retains its strong belief in the idea that maximum independence and full participation in life are vital components of well-being.

For more information on the history of occupational therapy, go to www.otcentennial.org

References:

Christiansen, C & Haertl, K (2014). A contextual history of occupational therapy. In Schell, B, Gillen, G, Scaffa, M, (eds). Willard and Spackman’s Occupational Therapy. (pp 9-34). Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

Christiansen, C. (2017) Foreword. In Anderson, L & Reed, K. (eds). The History of Occupational Therapy. The First Century. Thorofare, NJ: Slack, Inc. (Pp xiii-xvi.)

Anderson, L & Reed, K. (eds). The History of Occupational Therapy. The First Century. Thorofare, NJ: Slack, Inc.

Christiansen, C. (2007) Adolf Meyer Revisited. Connections between lifestyles, resilience and illness. Journal of Occupational Science, 14(2), 63-76.