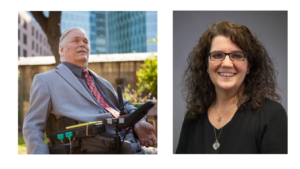

by Lex Frieden, NAB Convener, and Merrill Friedman, Sr. Director of Disability Policy Engagement, Anthem

Throughout July, we have celebrated the 30th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the first civil rights law that specifically protects individuals with disabilities. We expected to recognize it as a momentous occasion, with the excitement reserved for big anniversaries. The unexpected events of 2020 altered those plans, but we adapted and commemorated the ADA with Americans with disabilities and allies across the country through virtual platforms. As we focus on the pandemic and the much-needed conversations about equity in the workplace that the COVID-19 pandemic has stimulated, we are reminded that the ADA was designed for difficult situations like this. The ADA obliges us to create a society that equips all Americans with the tools they need to surmount the obstacles they encounter, especially when those obstacles loom large. The pandemic presents us with the opportunity to truly understand and embrace those principles.

The COVID-19 pandemic has altered how many Americans perceive accommodations for disability and has introduced many practices used by people with disabilities, like working from home, to everybody else. As these sorts of practices that were previously regarded as “special” accommodations become more accepted by employers, they will quite rightly be regarded as appropriate and typical, as the ADA intended.

While a key part of disability rights has always been about the choice to be present and participate in the larger community, functions like online delivery, telehealth, telework, and curbside services have also been a method utilized by the disability community to manage access barriers. The COVID-19 pandemic launched a surge of telemedicine that has brought health care to individuals in their homes, a safer alternative to in-person visits, and necessitated telework that has enabled some of us to stay employed by working from our homes.

The importance of these options has been pushed into the public consciousness. A new employee with a disability that needs to telework because of health complications or processing needs will likely have less difficulty justifying their ability to telework now that a significant number of Americans have seen its effectiveness. An employee with a hidden disability may never have considered requesting accommodations before but may now be aware that telework can serve as an accommodation as needed.

Physical distancing has also created an opportunity to address the lack of technological access that separates many Americans with disabilities from

Physical distancing can add another level of difficulty for individuals with disabilities who are still navigate an inaccessible world.

the increasingly important “information highway.” In 1990, the early days of the ADA, Internet commerce was still in its infancy, and most people did not have cell phones, much less smart phones. Now, Internet access is equally as important as physical access, and the COVID-19 pandemic has shined a light on how Internet inaccessibility can hamper commerce and inclusion, creating demand for better access. Using this momentum, we must continue to identify the practices that we wish to keep and further move the needle on increased access toward communities that work for everyone.

Perhaps the most important factor, however, has been the personal connection: each American now has the understanding of how difficult it can be to maintain what we think of as a typical life without access to social networks, goods, and services, as well as how this lack of access can affect our mental health. Open discussions of self-care and emotional well-being have become more common for all Americans. Considering that many Americans struggle finding effective ways to discuss mental health with their families, friends, and colleagues, these dialogues are a promising step toward increased acceptance.

President George H.W. Bush signs the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, surrounded by Evan Kemp, Chair of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission; Justin Dart, Chair of the President’s Committee on Employment of People with Disabilities; Sandra Swift Parrino, Chair of the National Council on Disability; and Rev. Harold Wilke, an ordained minister and disability advocate.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also highlighted systemic issues related to caregivers, another topic to which the disability community has consistently drawn attention for the past decade. The essential need for caregivers, the lack of resources to support caregivers, and the limited choices for in-home supports have gone from personal or familial issues to a nation-wide policy discussion. Once seen only as a niche issue for older adults and people with disabilities, caregivers’ access to resources has recently been a leading part of discussions as we talk about healthy futures and communities. We remain steadfast in our commitment to solving the problems surrounding the critical need for home and community-based services and community inclusion and putting an end to unnecessary institutionalization. As more Americans demand increased capacity in our communities to support people with long-term care and support needs, we must prioritize and resource options that enable people with disabilities to live in their homes, with their families, friends, and loved ones, while receiving quality services and supports.

While the 30th anniversary celebrations of the ADA may not be what we originally envisioned, the ADA and its values remain as important as they were 30 years ago, and we can witness their effects in real time. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the public is looking for solutions, and after more than 30 years of critical thinking about how to make our communities more accessible and more inclusive, the disability community has answers. We have an opportunity to take what we have learned since the passage of the ADA about accommodation and inclusion and share that knowledge with the larger population, ensuring a society that is equitable and accessible for all Americans.